Islam is an Abrahamic-monotheistic religion based upon the teachings of Prophet Muhammad ibn Abdullah (l. 570-632 CE, after whose name Muslims traditionally add “peace be upon him” or, in writing, PBUH). Alongside Christianity and Judaism, it is a continuation of the

teachings of Abraham (featured in both Jewish and Christian scriptures, considered a prophet in Islam, after whose name Muslims say, “peace be upon him” as well), although it does differ in some respects from both of these. The adherents of Islam are referred to as Muslims, of which there are around two billion in the world today, second only to Christians in number.

The Prophet’s Mission

The Prophet – Muhammad ibn Abdullah – was born in 570 CE. He was a member of the Quarshie clan of Banu Hashim, a highly respected faction despite their declining wealth. Orphaned at an early age, he was raised by his uncle Abu Talib, who is said to have loved him even more than his own sons. Muhammad became a trader and was renowned for his honesty (as it was a rare trait in Arabia in those days), and this honesty attracted the attention of a wealthy widow named Khadija who sent a marriage proposal, which he accepted, although she was 15 years older than him (he was 25 years of age at the time). Khadija’s support for Muhammad was instrumental in the Prophet pursuing his mission.

As he reached his late thirties, he began worshipping in seclusion, in a cave called Hira, in the mountain Jabal al-Nour (“Mountain of Light”), near Mecca. One day in 610 CE, the Angel Gabriel is said to have approached him with the first revelation from God – Allah (meaning “the God”). Muhammad is said to have initially reacted negatively to the revelation – he was perplexed and scared, he ran back home, shivering with fear – but later on he realized that he was a prophet of God.

Muhammad began preaching the oneness of God to his family and close friends, and afterwards, to the general public. Arabia was polytheistic at the time and so Muhammad’s preaching of a single god brought him into conflict with the Meccans whose economy relied on

polytheism (merchants sold statues, figurines, and charms of the various gods) and the social stratification it supported. The Meccans took serious measures to stop him but he continued to preach this new faith as he felt he owed it to God to do so. In the year 619 CE, he lost both his uncle Abu Talib and his wife Khadija (a date known to Muslims as The Year of Sorrow) and now he felt alone in the world and sorely grieved, a situation worsened by the persecution he experienced in Mecca.

Help came in 621 CE, however, when some citizens of Yathrib (later known as Medina), who had accepted Islam, invited the Prophet and his companions to come to their city. In 622 CE, Muhammad fled Mecca to escape plots on his life (a flight known as the hegira, which marks

the beginning of the Muslim calendar) and went to Yathrib. The city admired his teachings and wanted the Prophet to act as the ruler of the city and to manage its affairs. Muhammad encouraged his followers in Mecca to migrate to Yathrib, and they did so in batches. After most

of his companions had left, he migrated with a trusted friend of his (and future father-in-law) named Abu Bakr (l. 573-634 CE).

With their newfound base, the Muslims now wanted to strike back against those who had persecuted them. The Muslims started conducting regular raids or “Razzias” on Meccan trade caravans. These raids were technically an act of war; the Meccan economy suffered and now they were angered and decided to end the Muslims once and for all. The Muslims faced an attack from the Meccans at the Battle of Badr (624 CE) where 313 Muslim troops routed an army of around 1,000 Meccans; some credit this victory to divine intervention while others to Muhammad’s military genius.

After the victory at Badr, the Muslims became more than just a group of followers of a new religion, they became a military force to be reckoned with. Multiple engagements followed between the Muslims and other Arabian tribes, with a great deal of success for the Muslims. In the year 630 CE the doors of Mecca, the city from which they had fled in panic a decade earlier, were opened to the Muslim army. Mecca was now in Muslim hands and, against all expectations, Muhammad offered amnesty to all those who surrendered and accepted his faith.

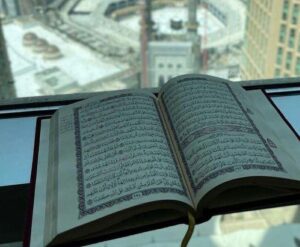

By the time of his death in 632 CE, Muhammad was the most powerful religious and political leader in all of Arabia. Most of the tribes had converted to Islam and swore their allegiance to him. He died in his own house, in Medina, and was buried there as well. The site has now been converted to a tomb named “Roza – e – Rasool” (Tomb of the Prophet), which lies adjacent to the famous “Masjid al-Nabwi” (Mosque of the Prophet) in Medina and is visited by millions of Muslims every year. The revelations which are said to have been given to Muhammad by the angel Gabriel were memorized by his followers and, within a few years after his death, were written down as the Quran (“the teaching” or “the recitation”), the holy book of Islam.

Quran, Sunna, & Hadith

1. Quran: The Quran is the holy book of Islam, believed to be the literal word of God (Allah) as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) through the angel Gabriel. It serves as the primary source of guidance for Muslims in matters of faith, practice, and morality.

2. Sunna: The Sunna refers to the actions, sayings, and approvals of the Prophet Muhammad. It complements the Quran and provides practical examples of how to live a righteous life. The Sunna is derived from the Hadith literature.

3. Hadith: Hadith are the recorded sayings, actions, and approvals of the Prophet Muhammad. They provide detailed explanations and context for various aspects of life, including religious practices, ethics, and legal matters. Hadith collections vary in authenticity, and scholars rigorously evaluate their reliability.

The Quran is the central religious text for Muslims. It is believed to be the literal word of God (Allah) revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) through the Angel Gabriel. The Quran serves as the ultimate source of guidance, covering matters of faith, morality, and

law. It contains timeless principles and divine instructions. Hadith, on the other hand, refers to the sayings, actions, and approvals of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). These were transmitted orally by his companions and later compiled into written collections. Hadith provides practical guidance on how to live according to the teachings of the Quran. It complements and clarifies the Quranic verses, offering context and specific examples.

The Sunnah encompasses the entire way of life of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). It includes not only his explicit teachings (Hadith) but also his tacit approval of certain practices. Following the Sunnah is considered virtuous and helps Muslims emulate the Prophet’s example. Sunnah covers various aspects of life, including rituals, ethics, interpersonal relations, and personal conduct.

Pillars of Islam

The acts of worship in Islam, or the “pillars” on which the foundation of Islam rests, are the formal duties that all people who choose Islam as their path must acknowledge and adhere to.

The Five Pillars of Islam are:

• Shahada (testimony)

• Salat (prayer five times a day)

• Zakat (alms/tax paid to help others)

• Sawm (fasting during the time of Ramadan)

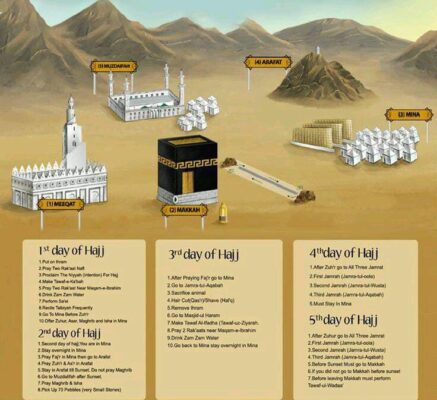

• Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in a lifetime)

The first pillar – Shahada – is essential for anyone to become a Muslim; it is the acknowledgment of oneness of Allah (God) in all attributes and is commonly expressed in the phrase: “There is no one worthy of worship but Allah (God) and Muhammad is Allah’s Prophet.” The concept of God in Islam dictates that he is beyond all imaginations (the pronoun “he” is merely a convenience for our use, in no way does it dictate any of his attributes) and the most supreme; his is whatever is in the universe, and everything submits to his will; so, therefore, must human beings in order to live in peace. In fact, the word “Islam” literally means “submission” as in submission to the will of God.

Importance of Pillars of Islam

Each of the five pillars work in tandem with one another to bring the essence of Islam as a religion of peace and submission to Allah SWT, into the lifestyle of every Muslim:

Monotheism and the belief in Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) as the last messenger of God is the central tenet of Islam around which everything else revolves, and reciting the Shahada (shahadah) in prayer each day serves to remind Muslims of this integral belief. Salah (salat) occurs five times a day, and offers five different opportunities for the remembrance of Allah SWT and our purpose in this life to worship Him.

The month of Ramadan requires every Muslim to abstain from their most basic needs and desires, like food, drink and sexual relations for a period of time each day. Every year, the Sawm gives Muslims the opportunity to gather control over their human needs. Without these distractions, Muslims can instead nurture good conduct and their connection to Allah SWT.

While Sadaqah (charity) is greatly encouraged to be a part of everyday Muslim life, it is obligatory to offer Zakat (alms) once a year, ensuring that wealth is continuously redistributed to those who are in need of it.

During the Hajj (pilgrimage), Muslims must each wear the same simple garments and perform the same ritual acts of devotion to Allah. Stripped of worldly distinction, people are reminded that all are equal before God.

Facts about the five pillars of Islam

• A Muslim must commit to each pillar and what it entails throughout their lives.

• Each pillar also accounts for those who may be unable to fulfill one or more of them, for example, due to ill health, menstruation or pregnancy, and a lack of financial means, amongst others.

Spread of Islam

Mecca, as noted, was originally the city that rejected Muhammad and his message but, later, became the heartland of the faith (as it houses the Ka’aba), while Medina, the city that welcomed the Prophet when none else did, became the capital of the empire. Arabia was located at the crossroads of the Persian Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) and the Byzantine Empire (330-1453 CE). As these two superpowers were almost constantly at war, in time, the people of Arabia suffered from the disruption of the region around them and, once united under Islam, launched a full-scale invasion into both of these empires to facilitate a rapid expansion of Islam.

The spread of Islam began in the early 7th century following the revelations received by the Prophet Muhammad in Mecca, leading to the establishment of a religious and political community in Medina. Islam expanded rapidly across the Arabian Peninsula, propelled by a combination of religious zeal, strategic military campaigns, and the appeal of Islamic teachings, which emphasized social justice, monotheism, and community solidarity. The Rashidun Caliphs, who succeeded Muhammad, played a crucial role in furthering the expansion, leading conquests that extended Islamic rule into the Byzantine and Sassanian empires. This expansion continued under the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, spreading Islam across North Africa, into Spain, and eastward into Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Trade, missionary efforts (dawah), and the spread of Arabic language and culture further solidified Islam’s presence in these regions, making it one of the world’s major religions.

Islamic Schism: Sunni & Shia

The Islamic schism between Sunni and Shia Muslims originated from a dispute over the rightful successor to the Prophet Muhammad after his death in 632 CE. Sunni Muslims, who constitute the majority, believe that the community should select the leader, or Caliph, and supported Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s close companion, as the first Caliph. In contrast, Shia Muslims hold that leadership should have stayed within the Prophet’s family, specifically through his cousin and son-in-law, Ali. This disagreement over succession led to political and theological differences, eventually solidifying into distinct religious sects. Over time, these differences expanded to include variations in religious practices, jurisprudence, and interpretations of Islamic history. The division has had profound political and social implications, contributing to conflicts and shaping the political landscape of the Muslim world throughout history.

Legacy of Islam

As the early scholars in the Islamic world agreed with Aristotle that mathematics was the basis of all science, the scholars of the House of Wisdom first focused on mathematics. Ishaq ibn Hunayn and Thabit ibn Qurrah, for example, prepared a critical edition of Euclid’s Elements, while other scholars translated a commentary on Euclid originally written by a mathematician and inventor from Egypt, and still, others translated at least eleven major works by Archimedes, including a treatise on the construction of a water clock. Other translations included a book On mathematical theory by Nicomachus of Gerasa, and works by mathematicians like Theodosius of Tripoli, Apollonius Pergacus, Theon, and Menelaus, all basic to the great age of Islamic mathematical speculation that followed.

The first great advance on the inherited mathematical tradition was the introduction of “Arabic” numerals, which actually originated in India and which simplified calculation of all sorts and made possible the development of algebra. Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi seems to have been the first to explore their use systematically and wrote the famous Kitab al-Jabr wa-l Qabalah, the first book on algebra, a name derived from the second word in his title. One of the basic meanings of Jabr in Arabic is “bone setting,” and al-Khwarizmi used it as a graphic

description of one of the two operations he uses for the solution of quadratic equations.

The scholars at Bayt al-Hikmah also contributed to geometry, a study recommended by Ibn Khaldun, the great North African historian, because “it enlightens the intelligence of the man who cultivates it and gives him the habit of thinking exactly.” The men most responsible for

encouraging the study of geometry were the sons of Musa ibn Shakir, al-Mamurl’s court astronomer. Called Banu Musa – “the sons of Musa” – these three men, Muhammad, Ahmad, and al-Hasan, devoted their lives and fortunes to the quest for knowledge. They not only sponsored translations of Greek works, but wrote a series of important original studies of their own, one bearing the impressive title The Measurement of the Sphere, Trisection of the Angle, and Determination of Two Mean Proportional to Form a Single Division between Two Given

Quantities.

The Banu Musa also contributed works on celestial mechanics and the atom, helped with such practical projects as canal construction, and in addition recruited one of the greatest of the ninth-century scholars, Thabit ibn Qurrah.

During a trip to Byzantium in search of manuscripts, Muhammad ibn Musa happened to meet Thabit ibn Qurrah, then a money changer but also a scholar in Syriac, Greek, and Arabic. Impressed by Thabit’s learning, Muhammad personally presented him to the caliph, who was in

turn so impressed that he appointed Thabit court astrologer. As Thabit’s knowledge of Greek and Syriac was unrivaled, he contributed enormously to the translation of Greek scientific writing and also produced some seventy original works – in mathematics, astronomy, astrology, ethics, mechanics, music, medicine, physics, philosophy, and the construction of scientific instruments.

Although the House of Wisdom originally concentrated on mathematics, it did not exclude other subjects. One of its most famous scholars was Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Ishaq’s father – known to the West as Joanitius – who eventually translated the entire canon of Greek medical works into Arabic, including the Hippocratic oath. Later a director of the House of Wisdom, Hunayn also wrote at least twenty-nine original treatises of his own on medical topics, and a collection of ten essays on ophthalmology which covered, in a systematic fashion, the anatomy and physiology of the eye and the treatment of various diseases which afflict vision. The first known medical work to include anatomical drawings, the book was translated into Latin and for centuries was the authoritative treatment of the subject in both Western and Eastern universities.

Others prominent in Islamic medicine were Yuhanna ibn Masawayh, a specialist in gynecology and the famous Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi – known to the West as Rhazes. According to a bibliography of his writings al-Razi wrote 184 works, including a huge

compendium of his experiments, observations, and diagnoses with the title al-Hawi, “The All-Encompassing.”

A fountainhead of medical wisdom during the Islamic era, al-Razi, according to one contemporary account, was also a fine teacher and a compassionate physician, who brought rations to the poor and provided nursing for them. He was also a man devoted to common sense, as the titles of two of his works suggest. The Reason Why Some Persons and the Common People Leave a Physician Even If He Is Clever, and A Clever Physician Does Not Have the Power to Heal All Diseases, for That is Not within the Realm of Possibility. The scholars at the House of Wisdom, unlike their modern counterparts, did not “specialize.” Al Razi, for example, was a philosopher and a mathematician as well as a physician and al-Kindi, the first Muslim philosopher to use Aristotelian logic to support Islamic dogma, also wrote on logic, philosophy, geometry, calculation, arithmetic, music, and astronomy. Among his works were such titles as An Introduction to the Art of Music, The Reason Why Rain Rarely Falls in Certain Places, The Cause of Vertigo, and Crossbreeding the Dove.

Another major figure in the Islamic Golden Age was al-Farabi, who wrestled with many of the same philosophical problems as al-Kindi and wrote The Perfect City, which illustrates to what degree Islam had assimilated Greek ideas and then impressed them with its own indelible

stamp. This work proposed that the ideal city be founded on moral and religious principles from which would flow the physical infrastructure. The Muslim legacy included advances in technology too. Ibn al-Haytham, for example, wrote The Book of Optics, in which he gives a detailed treatment of the anatomy of the eye, correctly deducing that the eye receives light from the object perceived and laying the foundation for modern photography. In the tenth century, he proposed a plan to dam the Nile. It was by no means theoretical speculation; many of the dams, reservoirs, and aqueducts constructed at this time throughout the Islamic world still survive.